By Mikasi Goodwin (June 22, 2018)

I was born and raised in Oregon, on colonized land, in a state founded specifically on systemic racism. I grew up poor. I grew up in a rural, conservative environment. I was very conservative for a long time. I am white, a trans woman, a lesbian, and a poor person. I say this to establish who is speaking, and what context I am speaking from.

When I was 13 I went to Bible Camp. Over a week away from home, our denomination’s pastors worked tirelessly to convert us. We were in church 3 times a day. Everything we did had a religious component, even when we went swimming or on hikes. By the end of the week, I felt sure that I was a sinner, that I was going to hell, and that I wanted to be saved. For the next few years I was a zealous believer in what I thought was the gospel, and what I thought was a lifesaving religious tradition.

I read the Bible fervently. I read commentaries, I studied & fasted. What I found wasn’t what I was taught to find. Time & time again I was getting a different message than my church. I was getting a message of liberation, of solidarity & of love from the gospel. Even immersed in conservatism like water, I couldn’t come to the same conclusions. This contradiction quickly led to a break with my church, and with Christianity in general. I spent a long time wandering & searching.

I didn’t find my way back to faith in a church service. It wasn’t reading the Bible that illuminated my own deeply held spiritual beliefs. God didn’t speak to me in the language of the church, in the scriptures & traditions of Christianity, or the acts of Christians I knew from my old church family. God spoke to me in the voices of people suffering under oppression, in prophetic voices unafraid to speak even the hardest truths. God spoke to me in the long struggle for liberation led by oppressed people. What did I find when I listened? I found that many oppressed peoples throughout the last 100 years have used a very specific tool to analyze their situation. That tool is called Marxism.

So, what is Marxism? That isn’t an easy question to answer. Marxism is about discovering the root of social problems, it is a radical way of analyzing the world. Marx says that ideas are the primary force that shapes our world but also that these ideas don’t come out of nowhere. These ideas are a product of human beings, of human societies, of our ‘material conditions’.

Marxism is about historical materialism. It says societies are divided into contradictory classes, slaves vs. slaveowners, lords vs. serfs, employers vs. employees. These are specific societal relationships that boil down to oppressor & oppressed. In my view, the goal of Marxist analysis is to find a way to transcend this relationship of oppressed & oppressor and create a liberated world.

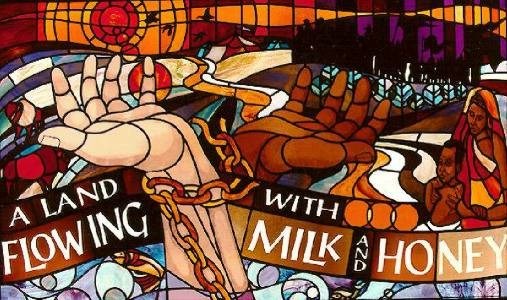

The idea of creating a liberated world is by no means new. A reading of the New Testament illuminates many similar ideas about transcending class in early Christianity. The Apostle Paul said, “There is no longer Jew or Greek, there is no longer slave or free, there is no longer male and female; for all of you are one in Christ Jesus” These words weren’t just a pretty spiritual allegory. The early church was known for distributing their wealth equally. In the book of Acts, it says, “All who believed were together and had all things in common; they would sell their possessions and goods and distribute the proceeds to all, as any had need.” Even Jesus said, “If you wish to be perfect, go, sell your possessions, and give the money to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven; then come, follow me… …Again I tell you, it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for someone who is rich to enter the kingdom of God.” The call of the gospel sounds awfully similar to Marx’s famous slogan, “From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs”.

Marxism & Christianity have often had an antagonistic relationship, but that antagonism is by no means universal. In Latin America in the 50’s & 60’s, an emergent group of Christian clergy members began to advocate for a fusion of Marxist analysis & Christian theology. The result? Liberation theology. Many of the concepts of liberation theology existed before its inception. Wherever the gospel was in the hands of the oppressed, especially in slave communities in the Americas, a type of theology of liberation sprang up. A theology that says to the oppressed, God is on your side. God is positioned as the liberator, the ultimate spiritual source of all struggles to free the slave & the captive. Liberation theology says to the Christian, you have a mission, a mission to establish the Kingdom of God on Earth, and that means nothing less than the unconditional liberation of all humankind. Jesus did not come to found a religion, but to spread the message of redemption, liberation and justice.

Liberation theology is a call to return to the historical mission of the Christian church & the gospel, abandoned by Christians as Christianity became co-opted and turned into a violent & oppressive institution. I am convinced this is the message modern Christianity needs. As young people leave the church in droves to wander the wilderness because they have been betrayed, abandoned & ignored by their faith communities, this theology calls them back in. This theology called me back in, a transgender lesbian who was completely abandoned by my faith community.

We need a theology of liberation. A theology of revolution, justice and love. We need a theology that demands of us that we feed the hungry, house the houseless and put our bodies on the line for justice. We need a theology that says to the oppressed, you are worthy, your voice is important. We need a theology that humanizes, that encourages solidarity, not just charity. A theology that says, “I will give up all I own to raise up the oppressed and empower them”. A theology that spurs us to act tirelessly to free people from the bondage of oppressive systems.

To be clear, this is not about electoral campaigns. This is not about legislation. You can’t elect liberation. You can’t legislate liberation. It takes a spiritual, cultural, and deeply personal shift among all of us. It takes a revolution. It takes an Exodus from the bondage of the United States to find redemption in building a new world, one without borders and nations. This is a long struggle, one that people in the Americas have been waging for over 500 years. It is by no means impossible.

Liberation theology is an expression of this long struggle. Faith in ancestors, faith in God, faith in deliverance from bondage & oppression has carried this long struggle into today. Many on the left have lost hope that they will see liberation in their lifetime, and many in faith communities have lost sight of the vision of liberation. What we can gain from each other is a vision for a better world, and the hope that will sustain us to build that better world in our lifetimes.

When the Israelites were struggling for their liberation from Egypt every attempt to crush them was made. Even when Pharoah’s kingdom lay in ruins, he chased them until the bitter end. We will face the same kind of entrenched resistance every step of the way, but I know that together, we can overcome any obstacle that stands between us & freedom.