Alexander Riccio is a labor organizer based in Corvallis, Oregon. He co-hosts the podcast LabourWave Revolution Radio and is currently collaborating with the Common Space Collective on a project to revive the commons in the Willamette Valley.

What are the sorts of experiences that led you to become a union organizer?

I am asked this question, or a variation of it, a lot and I find it’s very difficult to answer. I think this is because when people ask, ‘how did you become an activist’ or ‘how did you become an organizer’ they seem to actually be asking ‘what is the secret to change people from being passive to active?’ At the risk of disappointing such earnestness, I do not think there is a secret formula we can learn that will magically turn people into activists or organizers. The process by which someone becomes who they are is one which covers an entire lifetime. While I believe there are cataclysmic moments, or events, that inevitably occur in a person’s life that will change the course of their personal trajectory, I think these are often less important occasions in a person’s development than we might like to believe. The experiences of everyday life are the ones that shape a person, and these often take on the appearance of monotony or lull, so much so that we tend to neglect how important such everyday life is for shaping a person’s perspective and steering them towards a life of passivity or action.

For me, I grew up primarily in a working-class house raised by a single-mother. My class background is complicated, because there were years where my mother re-married and her spouse slowly rose up the class ladder during their marriage. So I remember in one year I moved six times across three different states from apartment to apartment, and then we began moving less and our moves turned from one apartment to another to one condo to a rental house to a mortgaged home. There were years of stability, and then those years changed again to precarious living.

My experience as an adult has been one of precariousness to a slow and steady improvement in my class conditions (though not in a linear way) to where now I am modestly comfortable, but still very much a part of the working-class. All of this, which likely seems unremarkable, I think is tremendously important for the development of my political worldview.

I also grew up in a home where abuse at the hands of a former step-father was very common, which forced me to encounter the true ugliness of what some might refer to as “toxic masculinity.” I call it patriarchy. This was part of my everyday experience, and all of these things have shaped me and ultimately steered me toward organizing.

There were momentous events, as well, that directed me to organizing. Again, I don’t think on the whole these events were as important as the experiences of my everyday life, but they were still significant. The most significant single event, I believe, which guided me toward organizing was Occupy Wall Street. OWS sprang to life when I was twenty-three years old, working in a pizza restaurant where I made $8.50 an hour and had no healthcare (which was a particular challenge for me as I have chronic asthma). No one had to convince me that we live in a class society, but until OWS no one was saying things like “We are the 99%.” Once I heard that slogan it clicked for me that my material conditions as a wage-earner with no social safety net was a political relationship.

At the time of Occupy I was not yet ready to dive into activism and be a part of the movement, but I visited the encampments in Atlanta a couple of times and listened to people talk about a range of topics, from police brutality to the oppression of women to the dominance of the ruling class (the 1%), and then shortly after my visits the entire Occupy movement was brutally crushed by police. It was shocking to me at the time, and I realize in hindsight how naive I must have been to be shocked, but seeing the news for a week-straight of encampment after encampment being broken up by police and people getting the shit kicked out of them is something I’ll never forget. If you ever want to see me get ruffled, which I’m typically a pretty calm person, just tell me about how much “freedom” we have in the US to criticize our government.

I had to process what happened during Occupy for a while, I feel like at least a year, and then it became clear to me that I needed to get involved.

Who would you consider your organizing heroes and what did you learn from them that inspires you?

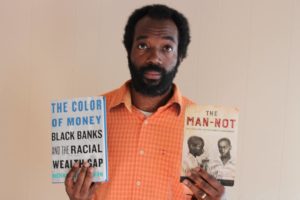

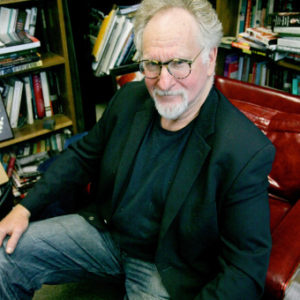

I’ve been very privileged in that I’ve had many great mentors who have helped guide me as an organizer. To sort of break the fourth wall here, two of my mentors who were quite honestly the biggest influences in my organizing are Tony Vogt and Joseph Orosco, the founders of the Anarres Project and two professors I had serve on my graduate school committee when I was a student. I also want to acknowledge Dr. Robert Thompson and Dr. Allison Hurst as great influences on me and my politics.

To me, there are two sides to the question of who are my “organizing heroes.” On the one side, there are those whose writings and political engagements have been inspiring and influential for me, and on the other side there are those who I have organized alongside that have inspired me and given me reason for hope. I feel that the latter are more foundational.

I’m impressed by the work of Jane McAlevey, Ursula le Guin, David Graeber, and many others. But, to sound a bit corny, my heroes are the ordinary people that I get to work alongside regularly. I’ve lived in Corvallis, Oregon now for over four years and I’ve been able to engage and work with so many people, and I continue to encounter new folks who are considerate and care about changing the world.

What inspires me the most is meeting someone and then getting to witness their own political development. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve met someone who is completely new to organizing, and maybe thinks politics is a matter of voting for either a Democrat or Republican, and then have witnessed them become radicalized and tremendous leaders. It happens all the time.

These experiences help recharge my energy, because it reminds me that there are potential radicals everywhere and people are capable of enormous personal growth. As well, the vast majority of people that I’ve engaged with in political conversations, even when at first they’ve seemed like a conservative or apologist for the status quo, have proven to be incredibly sensitive and compassionate. Nurturing those qualities of compassion and sensitivity is a primary task for organizers. If we approach organizing from a framework where we recognize people as dynamic and not static, that they’re politics are not fixed but always changing, then we can begin to start recognizing, as John Holloway puts it, “the rebellion in each and every one of us.”

Since we’re all potential agents of change, then we don’t really need to rely on the heroics of a few individual people to inspire us, and really we probably limit ourselves when we’re searching for those few famed heroes because likely the heroes we’re searching for are right in front of us all along.

What gives you hope for the future?

In addition to the things I’ve said about every person’s extraordinary capacity for change, what gives me hope is the fact that capitalism is not stable. Its power seems inescapable, but in fact the systems of domination we all live under are unstable and have many weaknesses.

I always make the following point when people slip into despair and fatalism, which is a particularly big problem for Leftist intellectuals (the ghost of Foucault perhaps): if capitalism were so absolutely powerful then why is it necessary to keep innovating techniques of surveillance and social control? In fact, why is it necessary for all the police and policing if the status quo were so total?

I make this point to highlight that capitalism is always having to conspire new ways of trying to control people because we are always rebelling against it, and as far back as written history one finds that there is a constant rebellion by ordinary people against any system of domination they live under. Silvia Federici points out that capitalism itself emerged as a counter-revolution to explosive liberation movements happening in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Maybe it’s just as plausible as any other claim about human nature to suggest that part of human nature is the refusal to be oppressed? The tendency latent in humans to refuse their subordination is something that continues to fuel my commitment to organizing, because while the future is not predetermined something we can reasonably assume as a given is that people will continue to fight against any forms of injustice we collectively encounter. Because of the human drive toward rebellion, capitalism is not stable. So that’s hope. The harder challenge is how to maximize such refusal into something at the scale we need to overturn this rotten system.

What do you think are the most significant obstacles to social/economic justice in the future?

I genuinely believe that the vast majority of people are capable of personal growth stimulated by their empathy for others, but what we encounter today is an incredibly isolating society where public space is steadily shrinking and the opportunities for people to connect with one another on a face-to-face basis are disappearing. When we are alienated in such a way, it becomes incredibly easy for people to dehumanize each other, because we don’t have to see each other’s lives and experiences as fundamentally human. In other words, attaining justice will require that we begin recognizing each other as human beings.

Part of how power is embodied is through the display of who gets to be considered human and who doesn’t. Within feminist theory there is the concept of “interpretative labor,” where what these thinkers have explored is how people who are oppressed are constantly in the position of having to identify the emotional needs of their oppressors. Oppressed people do this as a strategy for survival.

What this means is that we’re constantly looking through the gaze of the powerful in order to empathize with their so-called plight (consider here the despicable notion of the “white man’s burden” coined by Rudyard Kipling used as a pretext for invading foreign countries).

I remember one specific conversation I had in a classroom where I began talking about how difficult the labor and life of a farmworker is and how CEOs of big banks are not creating socially valuable goods that we can actually eat, and therefore we should be paying farmworkers more than CEOs when someone immediately said, “But those CEOs have hard jobs, and it can be really stressful to be a CEO.” What about the stress for the worker in the fields being paid poverty wages?

Coming back to my original point, I think these struggles to be recognized as human are really rooted in the structures of everyday life and the inability for people to have regular meaningful contact with one another. If we could start creating spaces where people can come together to relate to each other as humans, then I think we’ll begin making progress on these fronts.

Take up space.

Take it all.

I think one of our immediate tasks in fighting capitalism is to transfer as much private space as possible into public space, and as much public space as possible into the commons. And when we begin to start thinking about the commons, we can really enlarge our collective imagination about just what these spaces might look like and what they could mean. Common spaces could be seed exchanges and community gardens, open software programs and a collectively owned internet, they could be communes or cooperative workplaces, land trusts for sustainable farming or housing, and they could even be cooperatively owned laundry mats with free libraries and free educational classes.

The absence of shared spaces really fatigues our social movement energies, and I think if we begin to start creating spaces which can be for the purpose of organically reproducing our movement energies and relating to one another on a human level then we can shatter our collective alienation and really build a better world.

What books or movies would you recommend people study to learn about organizing and social change?

There are so many great books to read, but I’ll share a few that have been particularly impactful for me. John Holloway’s In, Against, and Beyond Capitalism; Jane McAlevey’s No Shortcuts: Organizing for Power; adrienne maree brown’s Emergent Strategies; Our Word is Our Weapon a collection of works by the Zapatistas, David Graeber’s The Democracy Project; Andrew Cornell’s Oppose and Propose; Grace Lee Bogg’s The Next American Revolution; and for a great encyclopedia of key radical terms and ideas I love the collection Keywords for Radicals: The Contested Vocabulary of Late-Capitalist Struggle.

For movies, the series Trouble put out by sub.media is spectacular and I love the films, Tout Va Bien with Jane Fonda and Z directed by Costa-Gavras. I also really like movies like It and A Bug’s Life because they have very clear messages on inequality and the power of collective action— just think about it.

But for all the great books and films one can learn about social movements, nothing really beats the education you’ll receive by getting involved with a group, whether that means joining an existing group or creating a new one. So for folks that are looking to gain more insights and education on how social change happens, the best way is to put yourself out there and start forming relationships with people in your area that are passionate like you are. I know for many this is daunting because we can feel like we don’t know enough, we’re not educated on political matters, we don’t have anything to say or our own original ideas, and we don’t have the experience all of which may make one feel very insecure. But, speaking as an organizer, I can guarantee you that you’re not alone in this feeling and the people that present themselves as super confident, cool, and knowledgeable on every little thing often are full of shit because we’re all really trying to figure this out as we go. Like the Zapatistas say, “walking we ask questions.”

(Interview with Joseph Orosco, February 2018)